The mainstream media are still trying to digest the proposed Google Books settlement. Of late, some of them have come to understand that one-sided news releases from Google’s lawyers might not be the full story.

There has been a gradual acknowledgment that Google is trying to rewrite copyright law to equate out-of-print with out-of-copyright. That is, just because a copyright owner chooses to take a book out of print does not mean the book is an orphan work. As long as the owner remains listed in the Copyright Office database with current contact information, it’s disingenuous to say the work has been abandoned.

But I have still not seen anyone with a large megaphone (unlike this little blog) address the central problem with all modern US copyright law, a problem created by Congress and the courts: The original purpose of copyright law is to encourage creation, not to provide annuities to corporations. Until we get back to that core principle, that it is the creator of a work that should benefit from copyright—not the corporation that strong-armed the rights away from that creator—people are going to remain confused about the correct moral course to navigate through these legal shoals.

What most people in the arts have in mind when they think about copyright is the right of the creator of a work to profit from it. What the publishers, entertainment conglomerates, and politicians have in mind when they think about copyright is the power of a corporation to coerce the creator to give up the right to profit in the long run in exchange for enough money to eat today, along with the resulting financial security for the corporation’s stockholders, who did nothing whatsoever to create the work in the first place.

So when we’re watching these debates in which people in expensive suits talk about their rights, they are talking about legal rights wrested from the grasp of the true possessors of the moral rights inherent in the act of creation.

European copyright law gets this. American copyright law doesn’t. Here, a corporation is a legal person with pretty much the same rights as a natural person—more rights in some instances.

I don’t know how much damage will transpire before politicians sit up and take notice. Time will tell.

occasional essays on working with words and pictures

—writing, editing, typographic design, web design, and publishing—

from the perspective of a guy who has been putting squiggly marks on paper for over five decades and on the computer monitor for over two decades

Sunday, April 05, 2009

Sunday, March 29, 2009

Book designer speaks

C.S. Richardson articulates the underlying conception of book typography as an invisible art on YouTube. Clip 1, Clip 2, Clip 3. He well summarizes much of what I often ramble about; if you are of a mind to design your own book, you could do worse than to listen to Richardson and take to heart what he says. He doesn’t know it, but he speaks for me.

Sunday, March 22, 2009

A people person

No, not me. A client. Two recent ones, in fact.

I encounter most of my clients at a distance. I’ve had projects that lasted several months and that involved long and complex discussions by email but few if any telephone conversations. This seems perfectly natural to me. It doesn’t work for everyone, though. I recently completed a small project for one local client and I’m in the midst of a large project for another, both of which could easily have been handled entirely by email. But both of these clients are people to whom personal, face-to-face contact is important—more important than the details of the work they’re paying for. They trust their own judgment of the person they make eye contact with and shake hands with more than they trust their judgment of the goods that person delivers. So they make up reasons to stop by. That’s fine with me; I enjoy meeting clients when there’s an opportunity to do so. And it’s an excuse to straighten up the living room.

But I tend to focus on the details of the work and sometimes forget that not everyone cares as much about those details as I do. One day I may be working with a client who admits to being a perfectionist; the next I may be dealing with one who, having shaken my hand, trusts me to produce good work and doesn’t care about the minutiae.

It’s all good.

I encounter most of my clients at a distance. I’ve had projects that lasted several months and that involved long and complex discussions by email but few if any telephone conversations. This seems perfectly natural to me. It doesn’t work for everyone, though. I recently completed a small project for one local client and I’m in the midst of a large project for another, both of which could easily have been handled entirely by email. But both of these clients are people to whom personal, face-to-face contact is important—more important than the details of the work they’re paying for. They trust their own judgment of the person they make eye contact with and shake hands with more than they trust their judgment of the goods that person delivers. So they make up reasons to stop by. That’s fine with me; I enjoy meeting clients when there’s an opportunity to do so. And it’s an excuse to straighten up the living room.

But I tend to focus on the details of the work and sometimes forget that not everyone cares as much about those details as I do. One day I may be working with a client who admits to being a perfectionist; the next I may be dealing with one who, having shaken my hand, trusts me to produce good work and doesn’t care about the minutiae.

It’s all good.

Sunday, March 15, 2009

Old whine, new bottle

A few months ago, book marketing guru Brian Jud invited me to contribute a column on interior book design to his bi-weekly “Book Marketing Matters” e-zine. In response to a request from one of his readers, I decided to collect those very short pieces and post them on my website, for the convenience of anyone who wants a slow, fairly nerdy tutorial on the traditional craft of putting words on paper attractively and readably. You can even read ahead a little bit (Shh! Don’t tell Brian). This is an ongoing series, so check back from time to time.

Tuesday, March 10, 2009

A typographic river dark and wild

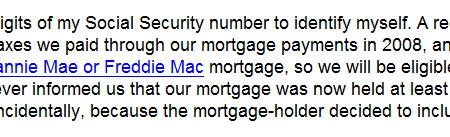

The image below was a random artifact in an RSS feed from the Editor Mom blog. It looks the way it does because of the width of my message window. That is, don't blame Katharine.

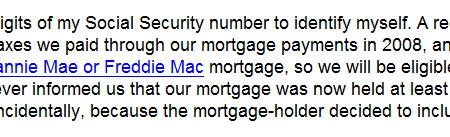

What it illustrates is something to check for on your typeset pages. The typical river consists of white space that travels down a paragraph from line to line, opening up a channel. But you also need to watch out for the darker sort of river seen here. Did you see it? If you’re not accustomed to thinking in terms of the color of the page, it may not jump out at you. Look at the word mortgage, running down the center of the image.

Details matter.

What it illustrates is something to check for on your typeset pages. The typical river consists of white space that travels down a paragraph from line to line, opening up a channel. But you also need to watch out for the darker sort of river seen here. Did you see it? If you’re not accustomed to thinking in terms of the color of the page, it may not jump out at you. Look at the word mortgage, running down the center of the image.

Details matter.

What it illustrates is something to check for on your typeset pages. The typical river consists of white space that travels down a paragraph from line to line, opening up a channel. But you also need to watch out for the darker sort of river seen here. Did you see it? If you’re not accustomed to thinking in terms of the color of the page, it may not jump out at you. Look at the word mortgage, running down the center of the image.

Details matter.

What it illustrates is something to check for on your typeset pages. The typical river consists of white space that travels down a paragraph from line to line, opening up a channel. But you also need to watch out for the darker sort of river seen here. Did you see it? If you’re not accustomed to thinking in terms of the color of the page, it may not jump out at you. Look at the word mortgage, running down the center of the image.

Details matter.

Sunday, March 08, 2009

I'm not hiring, but if I were...

India says it all.

And if you’re lucky enough to get a job somewhere, don’t forget Miss Snark’s list.

And if you’re lucky enough to get a job somewhere, don’t forget Miss Snark’s list.

Wednesday, March 04, 2009

Driving screws with a hairdryer

A member of a list I’m on posted a question about a tricky maneuver in Microsoft Word. This led to a question about why she needed to execute that particular maneuver, and it turned out she was preparing a document that was to be printed out on a laser printer to produce camera-ready copy for the printer.

What’s wrong with this picture?

A couple things, actually.

First, “camera-ready” copy is copy that will be photographed, using large sheets of film, as an intermediate step to making offset printing plates. This is a much more expensive process than direct-to-plate digital platemaking, which the vast majority of printers (and certainly all the large book and journal printers) switched to several years ago. So the publisher who assigned this task to the editor is stuck in a time warp with respect to printing technology and is likely paying far more to get its publications printed than it should be paying. There is really no excuse for running a publishing enterprise, even if it is a nonprofit organization, so lackadaisically that major technological revolutions pass by unnoticed.

Second, Word is not a page layout program. Let me repeat that, shouting this time: Word Is Not a Page Layout Program. No, it is a word processing program. It is the de facto standard program for manuscript preparation in the publishing business, whether it happens to be your favorite word processing program or not. And, truth be told, used properly, it’s a powerful program. Professional editors probably use more of Word’s advanced features than almost any other group, and it serves their purposes well. However, it is still a word processor. Attempting to use it to produce clean typeset pages (while I know there are some who have wrangled it into doing a half-decent job on simple text pages) is akin to driving screws with a hairdryer. Plugging in a hairdryer and turning it up to Hi does not make it any better a screwdriver than it was just lying there on the bathroom vanity.

If you have any connection whatever with the publishing industry, nothing I’ve said here should be news, nor should it be controversial. But apparently some folks haven’t gotten the message yet. Amateurs are forgiven. Professionals aren’t.

Harrumph!

What’s wrong with this picture?

A couple things, actually.

First, “camera-ready” copy is copy that will be photographed, using large sheets of film, as an intermediate step to making offset printing plates. This is a much more expensive process than direct-to-plate digital platemaking, which the vast majority of printers (and certainly all the large book and journal printers) switched to several years ago. So the publisher who assigned this task to the editor is stuck in a time warp with respect to printing technology and is likely paying far more to get its publications printed than it should be paying. There is really no excuse for running a publishing enterprise, even if it is a nonprofit organization, so lackadaisically that major technological revolutions pass by unnoticed.

Second, Word is not a page layout program. Let me repeat that, shouting this time: Word Is Not a Page Layout Program. No, it is a word processing program. It is the de facto standard program for manuscript preparation in the publishing business, whether it happens to be your favorite word processing program or not. And, truth be told, used properly, it’s a powerful program. Professional editors probably use more of Word’s advanced features than almost any other group, and it serves their purposes well. However, it is still a word processor. Attempting to use it to produce clean typeset pages (while I know there are some who have wrangled it into doing a half-decent job on simple text pages) is akin to driving screws with a hairdryer. Plugging in a hairdryer and turning it up to Hi does not make it any better a screwdriver than it was just lying there on the bathroom vanity.

If you have any connection whatever with the publishing industry, nothing I’ve said here should be news, nor should it be controversial. But apparently some folks haven’t gotten the message yet. Amateurs are forgiven. Professionals aren’t.

Harrumph!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)